|

Ground cherries didn't seem popular until a couple of years ago, but they've long been a favorite at our place. I grow the Aunt Molly variety although this year I will try a Peruvian variety as well. The taste is a bit hard to describe but it is a mild, sweet, slightly tangy taste like super mild sweet pineapple maybe? Ground cherries grow in husks, in a bush that hugs the ground and spreads out. They are very robust and we don't water them - once the seedlings are in the ground, we just let them be until harvest time. They fall off the bush before maturity. We plant them over fabric mulch - this makes harvesting much easier. We just raise the sprawling branches up and sweep all the ground cherries to the side to pick them up. We bring bucketfuls inside and they mature inside their husks. Once they are an orangey yellow, without any green hue, they are ready to eat. Ground cherries are about as sensitive to frost as tomatoes, definitely cover them or bring them in before the first frost. The seeds are very easy to save, Just put a few ground cherries in water in a blender or squish them by hand, scoop out the seeds and dry them. We love to snack on them as is. When we have an abundance, a few of the recipes I like to make with them include:

Unfortunately since ground cherries weren't as popular in the past, I haven't been able to find many safety tested canning recipes. I hope this changes soon... I often wish there existed more modern safe canning recipes.

0 Comments

For me, composting is mostly a sustainable and convenient way to dispose of food scraps. Sure, it's good fertilizer but the amount of compost we generate doesn't put a dent into what we'd need to fertilize the gardens. When I need a lot of compost, our neighbor drops off a tractor bucket or composted manure, or I order some.

When we first moved here, I started a compost bin outside. It was okay but a bit of a hassle to walk out and dump scraps, and we often procrastinated (especially in the wintertime) and ended up with a slimy bucket of scraps on the counter or even worse, fruit flies. Ever since I switched to vermicomposting (worm composting), those worries are over. I keep my worm bin next to the kitchen so it's easy to throw food scraps in as we go. To start vermicomposting, you need worms (you can order them online) and a worm farm or bin. There are many specialty bins available online, but, I'd rather make my own. I used two identical rubbermaid bins, one nested into the other. I drilled many, many holes in the inner bin, so that any excess liquid would drain out into the outer bin. Once my worms arrived, I put them in the inner bin along with some moistened bedding. I used coco coir (ordered at the same time as my worms) but there are many options. Once the compost is underway, I always keep about 3-6 inches of dry, shredded newspaper on top. I used to shred the paper by hand but I now use a paper shredder. This helps created a dark but airy environment for the worms, control humidity, and prevent fruit flies. The worms also gradually munch on it. Whenever I have food scraps, I lift up the shredded newspaper and add the food scraps in between the compost and the newspaper shreds. I don't have a lid on my bin. At first I did, but the lid made the bin too humid. The walls of the bins were covered in water and that made it very appealing for the worms to crawl up the sides and escape from the bin at night (they don't like light, so they don't escape during the daytime). Once outside the bin they would dry up and die. Not good! Once I stopped putting a lid on it, problem solved. The newspaper keeps it dark enough for them to be happy in the compost. There are many theories online about keeping the newspaper moist, but, I find that the lowest layer of newspaper gets moist just from absorbing moisture from the food scraps and compost. The top stays dry and the worms stay away from it. Once in a while, I throw in some eggshells grinded up in my food processor or mortar and pestle. The worms apparently need to eat this "grit" to help them grind up the food they eat. It's important not to overwhelm the bin with food scraps - the worms can only process so much. The worm population will adapt to the quantity of food you generate. However, in my case, when it's time to put up a lot of food (canning season), I have too much waste all of a sudden - in that case I put all the excess in my outdoor compost bin. But the rest of the year, the worm bin in sufficient. Every 1-2 years I harvest the compost. I have not found an easy way to do this. I used my 3D printer to print 3 sieves with holes of various sizes, that I designed to mimic the fabric screens people buy to make sieves. That allowed me to catch all the unprocessed bits of food (which I returned to the bin). But ultimately, I also need to do some hand separation of the worms and the compost. Since they run away from light, it's possible to scoop up the top layer of compost which will be worm less. By the time you put that layer into a bucket, the worms will have gone deeper and you can repeat that process. The worms need very little attention. Just topping up the shredded newspaper when it gets low. When we leave on vacation for a few weeks they don't need any special attention (don't overfeed them just before leaving - that's a recipe for fruit flies! Just give them the normal amount of food. They will keep busy processing leftover scraps and newspaper until you return. In this part of the world, the first gift we get from the land every year is maple syrup. We tap about a dozen trees most years. Mirroring our approach to everything else, we aim to harvest enough maple syrup to last us for the year and give a few gifts. Since that's a fairly small production, we keep things very simple and use as little specialized equipment as possible. To produce maple syrup our way, you will need:

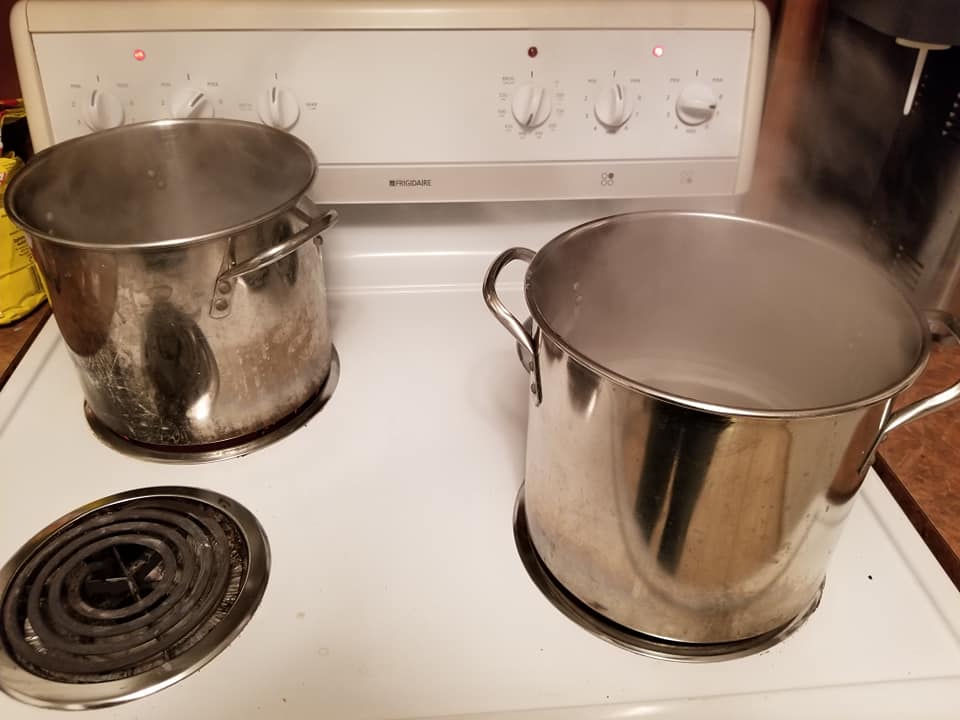

As a rule of thumb, when it's freezing at night and above freezing in the daytime, the maple sap will flow. Once we see a stretch of time in the forecast that will fit that pattern (usually around mid-March), we tap our trees. We drill holes about waist high, with a slight incline up, and hammer in a spile - it should fit snuggly but not be too hard to take out at the end of the season. We tap about a dozen trees. On a good flow day, that could fill two big buckets (50L in total) which is about the maximum we can pull up the hill on the sled comfortably. The sap flow isn't always predictable. There is more to it than the rule of thumb I mentioned above... it depends on how sunny it is, how wide the fluctuations are, and it seems to depend not only on the weather in the last 24h but a little bit longer too. The science of the maple sap flow is very interesting. Every couple of days we empty the pails into plastic buckets and carry them up the hill. We filter the sap through a jelly bag and boil the filtered sap in big stockpots. We simply boil the sap on our electric stove. This produces a lot of humidity, which is why a lot of people boil outside, but we don't worry about it too much since it's a once-a-year occurrence. We open the windows, it's nice to get some spring air in the house. Sometimes we ran the dehumidifier. Lots of people say that if you boil sap inside, your walls will be sticky but I haven't seen this to be the case at all. As the level drops, we had more sap. You'll be able to tell by the color that it's getting more concentrated. 40L of sap will make approximately 1L of maple syrup. Stick a thermometer in there once in a while - once you reach 4 degrees over the boiling point (for us that's 104 Celsius but it depends on your altitude), your maple syrup is ready. Keep a close eye on it as you get close to this reading, because maple syrup that is close to being done can very easily boil over (spill over the top of the pot) and that is a huge mess to clean up! We keep combining new sap into the pots over several days, it's easier not to burn it if you have a good amount in the pot. Sap will spoil so we refrigerate it or put it in a snowbank in between boils. Don't forget to sample the sap at various points during the boiling process! We call this "maple tea"! When the maple syrup is ready, I pour it into mason jars or whatever jars are on hand. I haven't found a safe canning procedure anywhere for maple syrup to make it shelf stable, so I store it in the freezer. I have had a bit of mold on it when I tried to store it at room temperature so I don't want to take any chances. I suspect you could use the same canning procedure as for canning simple syrup but I don't think it's been tested. We use maple syrup all year long for pancakes (which is a camping treat), hot beverages, one of my favorite family recipes, turnip maple soup and a new favorite, maple delicata squash

Last year for Earth Month, the Green Team at my place of work asked me to contribute a blog article for our employee intranet about how to grow your own food. I enjoyed writing that blog post so much that I decided to create my own blog. The original Earth Month article became the "top tips" page of this web page, which is an excellent place to start if you are new to my blog.

|

About this blogThis is where I share my learnings and adventures in homesteading Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed